Colleges tighten purse-strings, while students and faculty doubt value of online instruction.

Amidst a global pandemic caused by COVID-19, the future of academia is a hot topic and a sector of the economy that may never be the same. Students and faculty alike have had to adjust to unprecedented circumstances to continue learning and teaching. But while some have welcomed the new “normal,” others are quick to point out its flaws.

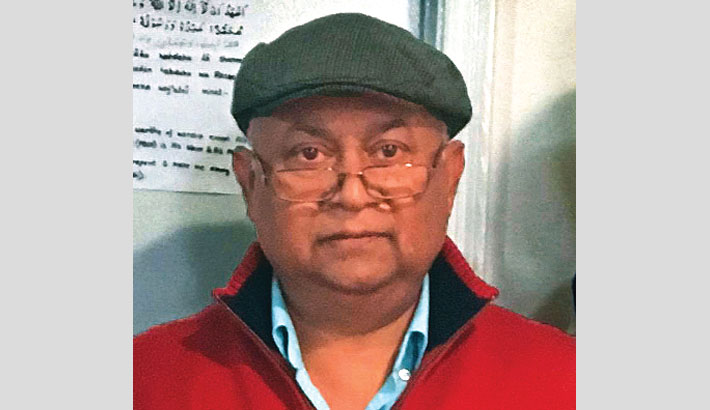

Dr. Nasir Ahmed, a professor in the Public Administration department at Louisiana State University, isn’t very fond of online instruction. “There are fewer networking opportunities. If everything becomes online, it will adversely affect people of lower income households in their pursuit of knowledge.”

“For some students, a school might be the only place for them to learn. Situation at home might not be the best and ideal for learning. I think it gives people who come from a financially sound background more of an advantage.”

However, for Dr. Ahmed, although he isn’t enamored with online teaching, the adjustment has not been terrible. The in-person lectures have essentially been replaced with more reading and writing assignments. Discussions have been moved online to Canvas, a learning management system that’s increasingly being adopted by schools across the board. Due to only teaching graduate level students, who he considers to be more mature, Dr. Ahmed admits his transition is probably easier than other professors at his school.

LSU has administered an optional Pass/Fail grading system like many other colleges nationwide. A key difference between life pre-pandemic and now, Dr. Ahmed says, is that he finds himself spending a lot more time working due to students calling, emailing, texting at all times, whereas previously he would just do his 3-hour classes and be done with all questions and concerns then and there. Flexibility, however, is an issue stressed by his university as a lot of people who attend the school have financial difficulties. In addition to the other flaws Dr. Ahmed has pointed out, he also believes that motivation is a more important factor in a world with online instruction.

Nishil Condoor, a sophomore at Saint Louis University, would probably agree with Dr. Ahmed on more than one point. “Online classes are worse in my opinion. I used to take 3-4 pages of notes in all my classes and now I rarely take over a page of notes per class.”

However, Condoor, who’s part of SLU’s engineering school, believes that online instruction still holds value. “I still see the same value — more in fact because we get to use our notes and resources which is applicable to the real world.”

Indeed, it is hard to envision a scenario where an engineer has to perform difficult math operations without the use of online tools, such as the multivariate calculators available at the click of a button. And yet that is the scenario for students come exam time in a math class.

For Chris Burns, an accounting major at Loyola University in Chicago, even the value falls subpar to expectations. “I think that the value I am receiving now with online classes is not as great compared to in-person classes because my teachers aren’t as accessible compared to when I’m on campus.”

“My classes that are based on discussion, like philosophy and ethics, aren’t quite as good while the other ones aren’t too different,” Burns added.

With the world in its current situation, uncertain times are ahead for higher education institutions. The CARES Act passed by Congress designates about $14 billion to higher education, which provides badly needed stabilization. Still, schools have started to take measures to protect their finances. Duke University, for instance, has pushed the freeze button on all new hires, expenditures, and raises for anyone earning more than $50,000. Many other institutions have taken similar precautions. Yale University even froze any new hiring until June 2021.

And as if the uncertainty wasn’t enough, questions of value for the mandatory alternative, online instruction, should strike more fear into colleges. About 1 in 6 high-school seniors who were expecting to enroll full-time into a college this fall are now taking a different route, a survey by the Arts & Science Group, a consulting firm for higher education, found.

Aly Lakhani, who attends Drexel University in Philadelphia, says that online classes are “easier in terms of completing the class, but it’s more difficult to learn the material since there’s hardly any structure.” Although many schools started to use Zoom as a tool for live lectures, the lack of uniformity and perhaps infrastructure has hurt the transition for college students.

Lakhani also doesn’t see the “same value” in online instruction because “it’s much easier to reply to other people on the internet for knowledge instead of learning it on your own.”With companies like Chegg, who provide digital services and resources for education, and Zoom, a mass and not-so-mass video conferencing company, spiking in user growth due to the pandemic, and Chegg’s CEO Dan Rosensweig advocating for online education on repeat, colleges and other academic institutions will be liable to make decisions in the next few months with significant, lasting impact on higher education.